|

||||||

|

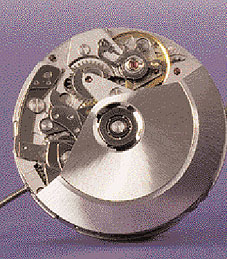

All mechanical chronograph movements with automatic winding came into being in the late 1960s and early 70s. This was a time when experts had long anticipated the quartz revolution. The very last of these to be made also turned out to be the most well-known and, by far, the most successful chronograph caliber of them all: the Valjoux 7750. It was unveiled on July 1, 1974, at the same time that the first solar cell watch became available in the U.S.A. This was also when the Japanese were producing the first large-series batches of quartz chronographs. Maybe watches in the Vallée de Joux simply ran differently. This high valley located in Swiss Jura, in the small village of Les Bioux, is where the blank movement factory of Valjoux SA made its home. Already two generations of watchmakers there had been producing very good to exceptional chronograph movements, though they never installed them in their own watches. All the big name Swiss watch houses purchased their chronograph calibers from Valjoux, and today just the mention of the caliber designations 72, 72c, and 88 will turn collectors into Pavlovian dogs. Just after the Second World War, slow beating (18,000 beats per hour) and manual-wind watches were on the way out, although they were still considered luxurious and exclusive. Two competing projects were underway to create the first chronograph movement with automatic winding. On March 1, 1969, Zenith won this very close race by unveiling the ultra-fast swinging (36,000 beats per hour) "El Primero." It edged out the micro-rotor module design from Heuer/Breitling/Büren. Valjoux hadn't so much lost the contest as slept through it. Five years later, when the Valjoux Caliber 7750 debuted, it didn't seem so advanced at first glance. Yet compared to its |

|

|

|

immediate predecessor models, the new 7750 sparkled with integrated automatic winding as well as numerous innovative solutions that cut production costs while ensuring greater reliability. The practical cam control of the chronograph functions was not seen as a disadvantage at the time. The more complicated and beautiful pillar wheel, by contrast, was viewed as a relic of the past. Complex parts such as the pillar wheel were expensive to produce. A company seeking to dominate the automatic chronograph sector would have to distribute its new movement quickly and in large numbers. Since the easiest way to do this was to offer the caliber at a reasonable price, production costs had to be slashed as much as possible. Part of these cost-cutting measures included replacing real screws with wedge connections. In addition, small individual bridges gave way to larger movement plates, under which other parts could be mounted and attached. The traditional design characteristics that we now associate with the higher watchmaking art - in part, because of the sophisticated marketing strategies of luxury watchmakers - could not be included in a utility movement intended for the general market. |

||