|

||||||||||||||||||||||

PAGE

ONE

INVISIBLE

HAND Luxury

Timepieces Get By STACY

MEICHTRY GENEVA -- In the

rarefied world of watch collecting, where Wall

Street investment bankers and Asian millionaires

buy and sell at auctions, a timepiece can command a

higher price than a luxury car. At an April event

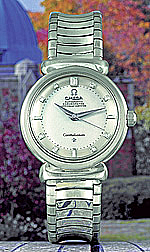

here, a 1950s Omega platinum watch sold for

$351,000, a price that conferred a new peak of

prestige on a brand known for mass-produced

timepieces.

Watch magazines

and retailers hailed the sale, at an auction in the

lush Mandarin Oriental Hotel on the River Rhone.

Omega trumpeted it, announcing that a "Swiss

bidder" had offered "the highest price ever paid

for an Omega watch at auction."

What Omega did not say: The

buyer was Omega itself. Demand and prices

for expensive watches have been surging, fed by

global economic growth. But there's another factor

behind the prices: an alliance between watchmakers

and a Geneva auction house called Antiquorum

Auctioneers.

Antiquorum sometimes stages

auctions for a single brand, joining with the

watchmakers to organize them, in events at which

the makers often bid anonymously. This is a

technique of which Patek Philippe and other famous

brands, as well, have availed themselves.

"It's an entirely

different approach to promoting a brand," says the

cofounder of Antiquorum, Osvaldo Patrizzi,

"Auctions are much stronger than advertising." Mr.

Patrizzi worked with Omega executives for two years

on the auction, publishing a 600-page glossy

catalog and throwing a fancy party in Los Angeles

to promote the event. "We are collaborators," he

says.

Auctioneer

Osvaldo Patrizzi, president and

co-founder of Antiquorum, left,

and Stephen Urquhart, president

of Omega, at the Omegamania

auction in Geneva on April

15.

But now there's

ferment in the world of watch auctions. First,

they're starting to raise ethical questions, even

within the industry. "A lot of the public doesn't

know that the biggest records have been made by the

companies themselves," says Georges-Henri Meylan,

chief executive of Audemars Piguet SA, a high-end

Swiss watchmaker. "It's a bit dangerous."

More unsettling,

Antiquorum's Mr. Patrizzi, who essentially founded

the business of watch auctions, is under fire by

the house he cofounded. Its board ousted Mr.

Patrizzi as chairman and chief executive two months

ago -- and hired auditors to scour the

books.

The business of auctions for

collectibles is not a model of transparency. The

identities of most bidders are known only to the

auction houses. Sellers commonly have a "reserve,"

or minimum, price, and when the bidding is below

that, the auctioneer often will bid anonymously on

the seller's behalf. However, the most established

houses, such as Christie's International PLC,

announce when the seller of an item keeps bidding

on it after the reserve price has been

reached.

Omega's

president, Stephen Urquhart, says the company is

not hiding the fact that Omega anonymously bid and

bought at an auction. He says Omega bought the

watches so it could put them in its museum in

Bienne, Switzerland. "We didn't bid for the watches

just to bid. We bid because we really wanted them,"

he says. Omega's parent, Swatch

Group Ltd., declined

to comment.

Through the auctions, Swiss

watchmakers have found a solution to a challenge

shared by makers of luxury products from jewelry to

fashion: getting their wares perceived as things of

extraordinary value, worth an out-of-the-ordinary

price. When an Omega watch can be sold decades

later for more than its original price, shoppers

for new ones will be readier to pay up. "If you can

get a really good auction price, it gives the

illusion that this might be a good buy," says Al

Armstrong, a watch and jewelry retailer in

Hartford, Conn.

Niche watchmakers

have used the auction market for years to raise

their profiles and prices, mainly among collectors.

As mainstream brands like Omega embrace auctions,

increasing numbers of consumers are affected by the

higher prices.

Omega and

Antiquorum got together at the end of 2004. The

watchmaker was struggling to restore its cachet.

Omega once equaled Rolex as a brand with appeal to

both collectors and consumers, but in the 1980s,

Omega sought to compete with cheap Asian-made

electronic quartz watches by making quartz

timepieces itself. Omega closed most of its

production of the fine mechanical watches for which

Switzerland was famed, tarnishing its image.

A decade later,

Omega tried to revive its luster by reintroducing

high-end mechanical models. It raised prices and

signed on model Cindy Crawford and Formula 1 driver

Michael Schumacher for ads. When this gambit failed

to lure the biggest spenders, Omega turned to a man

who could help.

Mr. Patrizzi, 62

years old, had gone to work at a watch-repair shop

in Milan at 13 after the death of his father,

dropping out of school. He later moved to the

watchmaking center of Geneva, at first peddling

vintage timepieces from stands near watch

museums.

He founded

Antiquorum, originally called Galerie d'Horlogerie

Ancienne, in the early 1970s with a partner. At the

time, auctions of used watches were rare, in part

because it was hard to authenticate them. But Mr.

Patrizzi knew how to examine the watches' intricate

movements and identify whether they were

genuine.

At first,

prominent watchmakers were wary. Mr. Patrizzi

approached Philippe Stern, whose family owns one of

the most illustrious brands, Patek Philippe, and

proposed a "thematic auction" featuring only

Pateks. The pitch: Patek would participate as a

seller, helping drum up interest, and also as a

buyer. A strong result would allow Patek to market

its wares not just as fine watches but as

auction-grade works of art.

The first Patek

auction in 1989 featured 301 old and new watches,

with Mr. Patrizzi's assessments, and fetched $15

million. Mr. Stern became a top Patrizzi client,

buying hundreds of Patek watches at Antiquorum

auctions, sometimes at record prices. The brand's

retail prices soared. Over the next decade, the

company began charging about $10,000 for relatively

simple models and more than $500,000 for

limited-edition pieces with elaborate functions

known in the watch world as "complications."

Patek began

promoting its watches as long-term investments.

"You never actually own a Patek Philippe," ads

read. "You merely look after it for the next

generation." Mr. Stern says he bid on used Patek

watches as part of a plan to open a company museum

in 2001. Building that collection, he says, was key

to preserving and promoting the watchmaker's

heritage, the brand's most valuable asset with

consumers. "Certainly, through our action, we have

been raising prices," he says.

Auctions

gradually became recognized as marketing tools.

Brands ranging from mass-producers like Rolex and

Omega to limited-production names like Audemars

Piguet and Gerald Genta flocked to the auction

market with Antiquorum and other houses. Cartier

and Vacheron Constantin, both owned by the Cie.

Financière Richemont SA luxury-goods group

in Geneva, have starred in separate single-brand

auctions organized by Mr. Patrizzi.

"Patek opened a

lot of doors for us, but we also opened a lot of

doors for Patek," he says.

Brands began to

vie for his attention, sending Mr. Patrizzi watch

prototypes to assess and, they hoped, occasionally

wear. They hired his assistants at Antiquorum as

their auction buyers, cementing ties. "He was a

kind of spiritual father for me," says Arnaud

Tellier, who worked under Mr. Patrizzi before

becoming Patek's main auction buyer and director of

the Patek museum.

Friends describe

Mr. Patrizzi as a rare intellectual in a market

with many coarser types. Guido Mondani, a book

publisher and watch collector who met Mr. Patrizzi

two decades ago, says he was charmed by the

auctioneer's encyclopedic knowledge of watch

history. Mr. Patrizzi began advising the publisher

on which watches to add to his own growing

collection, and wrote volumes on collectible

watches that Mr. Mondani published.

Mr. Patrizzi

discovered a rare defect in a Rolex Daytona owned

by Mr. Mondani: Its dial was sensitive to

ultraviolet rays and could change color. The result

was a sensation in the collector's world, with the

price of what became known as the Patrizzi Daytona

reaching nearly 10 times its retail price. Last

year, Antiquorum auctioned Mr. Mondani's Rolex

collection for about $9.4 million at current

exchange rates.

Mr. Patrizzi

himself amassed a collection of antique cuckoo

clocks and grandfather clocks, which grace his home

in Monaco. He recently built an Alpine chalet near

the chic French village of Megève and filled

it with clocks dating as far back as the 15th

century.

When he spoke to

Omega executives at the end of 2004, Mr. Patrizzi

felt that an Omega-only auction might be what the

brand needed to revive its image. There was one

problem. Antiquorum couldn't vouch for the

authenticity of watches that are mass-produced;

since they are worn more, their watch movements

have often been opened and tampered with in the

course of repair. So in an unusual arrangement,

Omega agreed to guarantee the authenticity of all

watches sold at the auction, and refurbish those

needing it beforehand. Omega supplied vintage

timepieces from its own collection for the

sale.

To build

interest, Mr. Patrizzi and Omega officials traveled

to 11 cities, hosting events such as a flashy party

at the Beverly Wilshire Hotel with celebrities such

as actors Charlie Sheen and Marcia Gay Harden.

Antiquorum and Omega joined in publishing the huge,

glossy auction catalog. When the sale, dubbed

"Omegamania," took place in April, it was shown on

jumbo screens at the BaselWorld watch fair and

streamed live on the Internet for online

bidding.

It brought in

$5.5 million. Besides the $351,000 platinum watch,

Omega outbid collectors on 46 other lots, including

many of the most expensive. Mr. Patrizzi estimates

Omega bid on 80 lots in all, out of 300.

A Singaporean

collector, told of Omega's role, called it

"heinous." Melvyn Teillol-Foo, who bid over the

Internet and bought a few pricey watches, added:

"If it turns out they bid against me and got me to

$8,000, I would be ticked off."

The auction is

boosting retail demand just as Omega is introducing

pricier models, says a Seattle retailer, Steven

Goldfarb. He says his top-selling Omegas used to be

$1,400 models, but Omegas costing three times that

are selling now. "Customers are conscious of the

fact that an Omega watch sold for $300,000," he

says. "They have no idea who bought it."

But just as Mr.

Patrizzi basks in one of his big successes, his

position in the industry is at risk. On Aug. 2, as

he vacationed during a traditional holiday time for

the industry, Antiquorum's board met and voted him

out as chairman and chief executive of the auction

house he cofounded. Mr. Patrizzi, who owns a

minority stake in the firm, says he learned of his

ouster from lieutenants who were locked out of the

company's Geneva headquarters the day of the

meeting, and later fired.

Named interim

chief was Yo Tsukahara, an executive at ArtistHouse

Holding, a Tokyo company that owns 50% of

Antiquorum. ArtistHouse then formed a different

Antiquorum board. Mr. Tsukahara hired auditors from

PricewaterhouseCoopers to scour Antiquorum

computers, financial records and inventory.

Pricewaterhouse wouldn't comment.

Mr. Patrizzi's

"thematic auctions" for a single brand of watches

weren't an issue, Mr. Tsukahara says in an

interview. They were a "win-win situation," he

says.

Mr. Patrizzi's

relations with ArtistHouse had been worsening for a

year. One issue was his resistance to adopting more

rigorous accounting in compliance with the Tokyo

Stock Exchange. Mr. Patrizzi opposed an ArtistHouse

push to replace Antiquorum's accountants, according

to Leo Verhoeven, a Patrizzi ally and an executive

at Habsburg Feldman, a Geneva company that owns 43%

of the auction house.

Mr. Verhoeven

adds that when Mr. Patrizzi stuck to the watch

industry's summer holiday schedule of mid-July to

mid-August, he caused a timing issue for

ArtistHouse, which landed on a Tokyo Stock Exchange

list for companies that don't report earnings

promptly enough. Mr. Tsukahara blames the delay on

Antiquorum, saying that auditors were unable to

account for several high-priced watches during an

inventory check, forcing ArtistHouse to write off

their value.

Mr. Patrizzi

denies watches were missing. Giving Mr. Patrizzi's

version, Mr. Verhoeven says two watches were

consigned to retailers and two were sold in private

sales that hadn't yet been booked because of an

accounting backlog. Messrs. Patrizzi and Verhoeven

say they have sought preliminary injunctions in a

Geneva civil court challenging the legitimacy of

Mr. Tsukahara's newly created board.

Mr. Patrizzi says

that days before his ouster, he sensed trouble was

brewing. The line of antique cuckoo clocks on the

wall of his Alpine chalet went "a bit out of

whack," he says. "One was 10 minutes too fast.

Another was 10 minutes too slow. I said, 'Oh God,

something is about to happen.'"

--Miho Inada in Tokyo

contributed to this article.

Write to Stacy

Meichtry at stacy.meichtry@wsj.com

How Top Watchmakers

Intervene in Auctions

Pumped Up in Bidding;

'It's a Bit Dangerous'

October 8,

2007; Page A1